By Steve Hammons

Basic training to work as a seasonal wildland firefighter consists of an efficient, nationally-standardized combination of classes referred to as the S-130 and S-190 training courses. This training is developed by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG).The NWCG coordinates interagency standards for wildland firefighting among federal, state, regional, and tribal agencies and operations throughout the U.S. The NWCG also produces training manuals for the wildland firefighter S-130/S-190 courses.

The courses are available at community colleges, vocational training centers, technical schools, high schools offering dual credit, stand-alone wildland firefighter training academies, and various agencies and organizations. Individuals applying for jobs as seasonal wildland firefighters must be at least age 18.

It’s tough, dangerous work. In recent fires in the West, some wildland firefighters needed to deploy their emergency shelters, which are far from 100 percent effective. Three firefighters were injured. Rescue helicopter crews have recently plucked wildland firefighters from very dangerous situations.

Yet, with overtime and hazardous-duty pay, and sometimes working 12-hour or 24-hour shifts (or longer in emergencies), wildland firefighters can earn substantial pay during the months of the fire season. They can also earn the satisfaction of working together as a team to help save forests, wildlife and domestic animals, homes, communities and human life.

TRAINING AND HIRING

The S-130/S-190 training for basic wildland firefighting includes four components:

- S-130: Firefighter Training

- S-190: Introduction to Wildland Fire Behavior

- I-100: Introduction to the Incident Command System

- L-180: Human Factors in the Wildland Fire Service

Passing a “work capacity test,” known as the “pack test,” is also a related part of the training and requirements. This fitness training and test are meant to simulate basic real-life physical requirements for extended trekking over rough terrain and vigorous work with hand tools, chain saws and other gear. The pack test for wildland firefighters involves:

- Completing a 3-mile hike

- While carrying a 45-pound pack

When the S-130/S-190 courses and pack test have been successfully completed, the candidate can apply for entry-level wildland firefighter jobs. If hired, the Incident Qualification Card or “red card” can then be issued which authorizes the entry-level wildland firefighter to work on the fire lines and other emergency situations.

In addition to the basic S-130/S-190 classes, many other advanced and specialized wildland firefighting training courses are also available through the NWCG.

Member agencies of the NWCG include the following:

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (U.S. Department of the Interior)

- Bureau of Land Management (U.S. Department of the Interior)

- Fish and Wildlife Service (U.S. Department of the Interior)

- Forest Service (U.S. Department of Agriculture)

- International Association of Fire Chiefs

- Intertribal Timber Council

- National Association of State Foresters

- National Park Service (U.S. Department of the Interior)

- United States Fire Administration (Federal Emergency Management Agency)

Jobs for seasonal wildland firefighters can be posted during the late fall and winter between September and December. Some hiring announcements may close in January, though hiring for upcoming fire seasons can continue through March.

HAZARDS AND FUTURE NEED

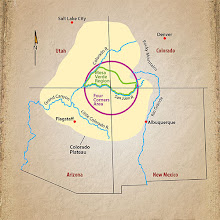

For many people, the 2017 Hollywood movie “Only the Brave” about an interagency hotshot crew was a window into the world of wildland firefighting. Josh Brolin, Jeff Bridges, Jennifer Connelly and Andie MacDowell were some of the actors portraying the Prescott, Arizona, community and a real-life hotshot wildand firefighting team.

The movie told the story of the 2013 Yarnell Hill Fire incident in central Arizona when 19 of the Granite Mountain Hotshots wildland firefighters of Prescott died, even though they had deployed their emergency shelters as they were about to be overrun by a wall of flames.

Interagency hotshot crews consist of 20-22 wildland firefighters who have enhanced training, equipment, experience, capabilities and readiness. According to the NWCG website, there are 68 hotshot crews nationwide, composed of 1,360 firefighters. Much like a small, forward military unit, they can operate in remote wilderness areas for extended periods.

Occupational hazards for all wildland firefighters can include breathing wildfire smoke, and sometimes the smoke from buildings, vehicles and other hazardous materials. Fatigue, stress, heat, rugged terrain, accident injuries and burned, falling trees pose additional dangers.

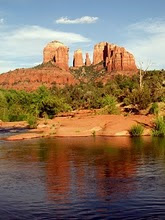

The severity of wildland fires has also been increasing, as reflected in the current fires in the West. A record amount of acreage has been burned, as well as many homes and communities. Lives have been lost.

These patterns seem to indicate that there will be an increased need for a more-robust force of seasonal wildland firefighters in the years to come.

For more information: