By Steve Hammons

There’s a rumor out there that life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are rights that are given to us by a higher Creator, not by governments, government officials and bureaucracies, kings or dictators.

If this is so, we might be unwise to surrender our personal, family and cultural history to judgments from government officials, politicians and bureaucracies. As a result, this path of independent thinking might make us hesitant to rely on national, state and tribal government officials to tell us who we are and who we are not.

These kinds of concerns have emerged in recent days regarding the three Cherokee groups recognized by the U.S. government.

Politicians from national and tribal government have attacked Americans who might or definitely do have Cherokee or other Native relatives and ancestors somewhere in the family tree. And Native Americans with a chip on their shoulder (understandably) have voiced righteous indignation about the "hijacking" of their identity and culture.

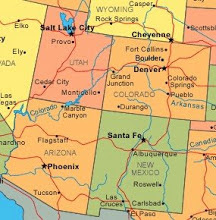

Journalists, pundits, political operatives, propagandists and well-meaning observers have weighed in too, often with little knowledge of Cherokee and U.S. history. Many or most of these people also likely have little or no direct experience themselves with Cherokee culture, either in the Oklahoma region or in the southern Appalachian Mountain Range, the ancient ancestral homeland.

Many people are not aware of the robust amount of intermixing between Cherokee and Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish newcomers in the Appalachian region in the 1700s.

So which is it? Does a Great Spirit of some kind give us these truths? Or, do national and tribal politicians, pundits and propagandists tell us who we are?

Do these truths flow from the grassroots up through the lives of generations of our ancestors into who we are? Or are these realities interpreted and defined from the top down, from government officials and others?

GROUP THERAPY

In human history and in our contemporary world there are many circumstances where governments, kings and dictators tell people a number of things about themselves.

They may tell people that they have no right to free speech or a free press, no right to self-government and democracy, no right to honest and ethical government officials, no right to education, no right to cultural identity, no right to human dignity, that their status in society is to be subservient or even that of a slave, or that they are sub-human.

Native Americans, of course, have been on the receiving end of this over the centuries. They are not the only ones.

Today, tribal sovereignty and self-government are important. The long, bloody and dark history of U.S. government and civilian actions against Native people proves that.

But government bureaucracies of all kinds can have hidden dangers that require constant vigilance, as do government officials and politicians. Surrendering our own judgment, insights and power to governments and government officials can be unhelpful and counterproductive.

Additionally, in organizations and social groups, people are often defined as either in the group or outside of the group."I’m in the good group and you’re not.” “I’m included, you’re not.” Or, “You’re in the bad group and I’m in the good group.” “You are not like me – you are the ‘other.’”

This seems to be the way of human nature and the human condition.

And this kind of human psychology and behavior probably plays a part in discussions about Cherokee and Native American lineage. Once we recognize this perceptual and behavioral pattern, it might help us see the larger situation more accurately and comprehensively.

STORYTELLING, AWARENESS, PERCEPTION

Over the last week, it has been interesting to see so many politicians and political operatives voice such deep concerns about Cherokee and Native American people. Who knew that certain national politicians, political pundits and media propagandists held such heartfelt concerns about the well-being of Cherokee people?

These politicians and operatives must be the good people I’ve heard about who are fighting for human decency in American and international society, and for justice, truth, freedom of speech and press, a decent way of life for all people, a better world and human progress of all kinds.

Or, could it be that these political operatives are using a number of well-meaning Cherokees, other Native Americans, journalists, observers and those suffering from "white guilt" for larger and darker purposes?

Beware of the “useful idiot” trap. This refers to the manipulation of unsuspecting people to serve clandestine, covert, deceptive and often dark objectives. Sometimes it’s not very covert, but rather obvious, and it does take somewhat of an idiot to not realize it.

In these times of “information warfare” and manipulation here at home and around the world, it’s probably helpful for all of us to develop better skills in awareness and perception. Some people call it “situational awareness” or "situation awareness" – what are all the moving parts going on around us, what’s going to happen next, how should we react or handle it?

This Cherokee issue is just one of many that we need to make good judgments about based on good situational awareness.

It might also be helpful for us to be aware of “weaponized storytelling” or “weaponized narrative.” This method of persuasion is subtle and even unconscious for the reader, viewer and information consumer.

Sometimes we have to be able to see through the BS.

The story of the Cherokee is much deeper and wider in scope than is generally known. And that scope certainly includes the story of the mixing and blending of Cherokee with the early Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish explorers, hunters, settlers and generations of their descendants in the Appalachian region and elsewhere from the 1700s to today.

To deny this reality denies a crucial part of the Cherokee story, and of the American story.

(If you liked this article, please see my other recent ones about the Cherokee on the Joint Recon Study Group and Transcendent TV & Media blogs.)

Saturday, October 20, 2018

Americans with Cherokee roots can't rely on government bureaucracies to define them

Tuesday, October 16, 2018

Does tribal government politician speak for all Americans with Cherokee ancestry?

By Steve Hammons

In response to a national discussion about the history of the Cherokees and the intermixing of Cherokee with European-Americans (notably Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish in the 1700s), the secretary of state of one of the three federally-recognized Cherokee groups issued a public formal statement.

In his statement, Chuck Hoskin, Jr. made some accurate and helpful points. However, a closer look at his comments might provide insight.

Here is Hoskin’s complete statement, with my paragraph breaks for analysis:

"A DNA test is useless to determine tribal citizenship. Current DNA tests do not even distinguish whether a person's ancestors were indigenous to North or South America.”

“Sovereign tribal nations set their own legal requirements for citizenship, and while DNA tests can be used to determine lineage, such as paternity to an individual, it is not evidence for tribal affiliation.”

“Using a DNA test to lay claim to any connection to the Cherokee Nation or any tribal nation, even vaguely, is inappropriate and wrong. It makes a mockery out of DNA tests and its legitimate uses while also dishonoring legitimate tribal governments and their citizens, whose ancestors are well documented and whose heritage is proven.”

“Senator Warren is undermining tribal interests with her continued claims of tribal heritage."

BREAKING IT DOWN

Let’s take a look at Hoskin’s points one at a time:

- "A DNA test is useless to determine tribal citizenship. Current DNA tests do not even distinguish whether a person's ancestors were indigenous to North or South America.”

Some tribes determine membership by “blood quantum,” percentage of Native heritage and some, like the Cherokee, use historical census rolls. Hoskin is correct that DNA tests are not used to determine legal membership in federally-recognized Native tribes and groups.

However, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, to whom Hoskin was directing his comments, never indicated she felt she was eligible for official tribal membership. She states this was just something passed down in her family that she and other family members found worthwhile.

[Update: According to news reports, Warren identified herself as "American Indian" on a Texas Bar Association document.]

- “Sovereign tribal nations set their own legal requirements for citizenship, and while DNA tests can be used to determine lineage, such as paternity to an individual, it is not evidence for tribal affiliation.”

That is also true. Native tribes and groups set their own rules for who is in and who is out for official membership. Tribal governments as well as the U.S. government and various lawsuits also have been part of determining criteria for membership in various tribes. As noted, these criteria vary among tribes, and have changed and morphed over the years.

- “Using a DNA test to lay claim to any connection to the Cherokee Nation or any tribal nation, even vaguely, is inappropriate and wrong. It makes a mockery out of DNA tests and its legitimate uses while also dishonoring legitimate tribal governments and their citizens, whose ancestors are well documented and whose heritage is proven.”

Many Americans who suspect Cherokee or other Native American background in their family trees may disagree with Hoskin when he says it is “inappropriate and wrong” for any Americans to use a DNA test to research these issues.

Is it also wrong to study our ancestry and geneaology using public records and other research? Is Hoskin saying that if we conduct such research and it happens to confirm or discover "any connection to the Cherokee Nation or any tribal nation, even vaguely" that this is also "inappropriate and wrong," as Hoskins states?

What about research and DNA tests about our other ethnic and ancestral backgrounds from around the world?

It seems unclear why Hoskin states that Americans interested in their heritage who take a DNA test are “making a mockery out of DNA tests,” and “dishonoring legitimate tribal governments and their citizens, whose ancestors are well documented and whose heritage is proven.”

Again, if we do family history research other than DNA tests, is that also "dishonoring legitimate tribal governments and their citizens, whose ancestors are well documented and whose heritage is proven," as Hoskins states?

- “Senator Warren is undermining tribal interests with her continued claims of tribal heritage."

Like tens of thousands of Americans, Warren heard family stories of Cherokee background in the family tree. She valued this possible background, like many people. How this is “undermining tribal interests” also seems unclear.

FULL-BLOOD CLUB

In recent years, sometimes with a valid basis, Americans of various ethnicity have looked into Native American heritage in their family backgrounds.

Full-blood and other Native Americans sometimes say these are white “wannabe Indians” who are “appropriating” or "hijacking" Native cultures.

What exactly gives these “official Indians” the right to tell Americans who may very well have Cherokee and other native DNA within them that they have no right to explore and embrace this genetic background within themselves, their families and their ancestors?

The truth is that many members of the three U.S. government-recognized Cherokee groups have mixed-ethnicity of Cherokee and white, often Scots-Irish.

Does a person whose parents were both full Cherokee have more rights and insights than people whose Cherokee lineage is from a great-great-grandmother or a great-great-great-great-grandfather?

The science of DNA has its mysteries and is not fully understood. It apparently does not does not work like a math problem. Biological and other traits we may have inherited from our ancestors do not necessarily work according to mathematical formulas and fractions.

Culturally and socially speaking, of course people raised on reservations and Native nation lands have grown up immersed in Native culture. That goes without saying. And many have also lived the related collective trauma, difficulties and viewpoints.

They've also experienced the sometimes convoluted and questionable politics of Native tribes and leaders over the years – including the significant infighting and fracturing of the Cherokee culture over the decades and centuries.

Does Hoskin have the right to tell millions of Americans with Cherokee ethnic background that they don’t make the grade to join his organization? Yes.

Does he also have the have the right to tell them that they are not worthy of exploring and embracing their Native heritage?

(If you liked this article, please see my other recent ones about the Cherokee on the Joint Recon Study Group and Transcendent TV & Media blogs.)

Monday, October 15, 2018

Many Americans have Cherokee in the family tree

By Steve Hammons

Many Americans have Cherokee DNA within their genetic makeup.

Some families are aware this, some people have heard rumors or stories from family members and some are totally unaware of it. Did great-great-great-grandma really have a Cherokee parent?

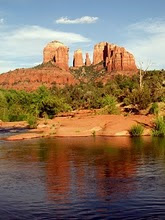

There may be many more Americans with Cherokee DNA in them than of other tribes. This is because Cherokees began intermixing with Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish explorers, hunters and trappers in the Appalachian region at an early phase in American history – much of it in the early- and mid-1700s.

This created a wide dissemination of Cherokee DNA into many American family trees.

Socially and culturally, many of these developments in the 1700s occurred before some of the more widespread efforts at domination, removal and near-genocide of Native American people later on, though these elements were well underway even in colonial times.

By the time of the infamous forced removal called the Trail of Tears in 1838-39, there were already several generations of mixed-ethnicity families living in the Cherokee mountain regions of what we now call North Carolina, Tennessee and surrounding areas that now include the current states of Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. Many had Scottish or Anglo names, lighter skin and prosperous farms.

Prior to the Trail of Tears, many Cherokee had headed west to Arkansas and elsewhere. Many were able to avoid detention and removal, and stayed in the Appalachian region where the federally-recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is still located at the Tennessee and North Carolina border.

Because of the mixed ethnicity and, in many cases, Anglo or Scottish names, some of these people could “pass as white." And many may have chosen to do so in order to stay near their home region, or even as they moved west.

WHO ARE WE?

As we know, over the decades and centuries, people from many nations and cultures have arrived North America. The mixing of different ethnic groups here has been a fact of life for generations. Many of us can count at least a half-dozen or more different nationalities and ethnic groups in our family background.

And the more this blending has continued with each generation, the more likely that Cherokee or other Indian DNA is within many of today's American families.

Many don’t know about a Cherokee or Native American ancestor because that side of the family sometimes may not have detailed written records. Maybe relatives didn’t want to talk about “the Indian in the family” or the connection was forgotten or overlooked.

Today, some tribes use what is called the “blood quantum” to identify who has enough Indian “blood” in them to be official tribal members. Often, one-sixteenth blood quantum will qualify a person for official tribal membership.

So, if grandparents, great-grandparents or great-great-grandparents had some significant measure of Indian blood, based in these blood quantum measurements, a person can or cannot be considered a tribal member

To say that someone who is one-eighth is more Cherokee or Native American than a person who is one-sixteenth makes us wonder about the validity of looking at this in terms of mathematical fractions and percentages.

Most likely, a certain genetic background does not affect a person strictly by percentages. If you are one-quarter, one-eighth, one-sixteenth, one-thirty-second, one-sixty-fourth, does that mean the genetic history within you, which goes back into the ancient past, is not valid?

The idea of racial “blood” is, of course, outdated. We now know that our genes and our DNA helix are within every cell of our bodies. We are just scratching the surface of learning what is contained within them and how they function.

The genetic history of our ancestors is passed down over the centuries. It comes together in a child in certain ways, creating certain physical characteristics, and, we suspect, possibly psychological and personality tendencies.

The DNA within each cell of our bodies might act in ways we do not fully understand.

Does having a great-great-great-grandmother or -grandfather who was Cherokee instead of full-blood parents make you less Cherokee? In some ways, maybe yes. In other ways, this might not be so clear.

In some people, maybe this forgotten or hidden DNA is it is “sleeping.” For others, they may have always felt there was something in them connected to the ancient times in the Americas. They might even have slightly darker skin, a certain facial or body structure or other genetic traits. This background may manifest itself a little or a lot.

DNA MEMORIES?

Modern research into the nature of DNA has led to discoveries about this material within each cell of our bodies. DNA has important implications for who each one of us is, on many levels.

Once we have identified the various elements of our family tree and our genetic background, and possibly discovered or suspect Cherokee or other Native American connections, what should we make of it?

The DNA within all living things is the blueprint for what each organism becomes, subject to the environmental influences that can also have significant effects. It determines our physical characteristics and even our vulnerabilities to certain diseases.

For humans, recent discoveries about DNA are rapidly changing our views about the importance of this material. DNA may affect us much more significantly than we imagined. And, it may hold keys to further discoveries.

Is it possible that the DNA helix holds some form of important memories of our ancestors? Back in the 1960s, some psychological researchers claimed that there may be keys that unlock our deep DNA, revealing experiences of past generations.

It has been demonstrated that experiences necessary for survival of a species, even very tiny and simple organisms, are learned and that this knowledge is passed on to subsequent generations genetically.

For humans, with our relatively complex brain, feelings and memories, what other kinds of experiences might be saved in our DNA over the many thousands of years when our ancestors were born, lived, survived and died? Do these influences manifest themselves within us? And how?

Scientists are gradually uncovering the secrets of our DNA. They have mapped much of the DNA helix of not only humans, but other animals and plants. Many human genes remain a mystery and their purpose is unknown.

The idea that deep and ancient memories of our ancestors lie within our own bodies, within our DNA, seems far-fetched. Yet, in the field of genetics research there seems to be so much that is not known that, for an open-minded person, these kinds of theories about deep DNA memories probably cannot be ruled out.

Maybe it is time to consider the depth of our family trees and all of their complex branches and roots throughout time and the development of the human race. Whether Cherokee or other interesting ethnic backgrounds are deep within us, this certainly seems worth exploring.

In this sense, the official and legal definitions of who is Cherokee or part of some other Native American tribe and who is not become less relevant.

If a child in your family were to ask, “Am I part-Indian?” what would your answer be? Do you know for certain?

To find these answers, we can conduct research through DNA tests, genealogy records, by asking older family members and other kinds of investigation.

We can also listen to the voices of our DNA and our ancient ancestors within us.

(If you liked this article, please see my other recent ones about the Cherokee on the Joint Recon Study Group and Transcendent TV & Media blogs.)