At the junction of the Ohio River and the Hocking River in southeastern Ohio in 1774, the then-King’s governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, established a forward base as part of “Dunmore’s War” against the Shawnee and other tribes of the region in the months, weeks and days before the American Revolution.

In a planned two-pronged attack on the Shawnee in the southern Ohio and Ohio River Valley area, Dunmore’s force of approximately 1,700 men traveled from Fort Dunmore (Pittsburgh) to rendezvous with a Virginia colonial militia force near what is now Point Pleasant, West Virginia. (Fort Dunmore was previously known as Fort Pitt, and Fort Duquesne under the French.)

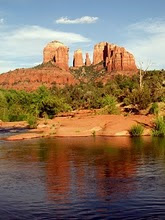

But for some reason, including suspicious ones, Dunmore chose to stop short of Point Pleasant, and built a base camp he named Fort Gower, 45 miles up the Ohio River. Dunmore built Fort Gower at the mouth of the Hocking River, originally called the Hockhocking by Native people. That location is now the village of Hockingport in Athens County, Ohio.

Dunmore sent a message downriver to militia Col. Andrew Lewis, commander of a force of about 1,000 men who had proceeded toward Point Pleasant. Dunmore told Lewis that he had changed plans and was now going to attack some Shawnee towns deeper in southern Ohio instead of joining forces with Lewis’ militia at Point Pleasant.

As the militia force arrived in the Point Pleasant area, without Dunmore joining them, the Shawnee and some Mingo and Lenape (Delaware) allies attacked. Shawnee Chief Cornstalk led between 300 and 500 warriors in a fierce, prolonged and bloody battle – but were defeated by the colonial forces.

DIVIDE AND CONQUER

Lord Dunmore was John Murray, a Scotsman with the title 4th Earl of Dunmore. He was appointed as colonial governor of New York from 1770 to 1771 and of the Virginia colony in 1771. He advocated for and launched a series of attacks into the Shawnee and other American Indian lands abutting the Ohio River Valley and southern Ohio, known as Dunmore’s War.

By 1774, Dunmore was also ruling over restless colonists who were increasingly unhappy with British control. On the western frontier of the Appalachian Mountain Range, settlers and those seeking more land were also starting to resist British governance, laws and taxes.

New arrivals to the colonies were heading west, trying to acquire land and a better life. In doing so, they pushed deeper into the lands of the Shawnee, Cherokee and other Native people who had lived there for thousands of years.

The Cherokee did not join the Shawnee, Mingo and Delaware warriors at the Battle of Point Pleasant, also called the Battle of Kanawha, even though the original Cherokee land then extended into the far western side of what is now West Virginia. In fact, Cherokee territory extended up to the exact area of Point Pleasant on the Ohio River, also then known as the Ohi yo or Ohiyo.

Why didn't Cherokee warriors join the fight? Part of the reason might be that British government agents were active among Indian tribes, trying to manipulate alliances and loyalties – and divide and conquer.

The Shawnee and Cherokee also had somewhat different cultures. The Shawnee to the north were patrilineal and the Cherokee to the south had a matrilineal society. Another probable and related reason might have been that Cherokee women had been voluntarily intermarrying with Scottish, Scots-Irish and Anglo newcomers since earlier times of friendly contact.

In the Cherokee tradition and culture, these men joined their wives’ matrilineal clans. Children of these marriages were also members of mothers’ and maternal grandmothers’ matrilineal clans.

The two tribes' languages also had different roots. The Shawnee spoke an Algonquian-based tongue that was widely used in the north-central regions of North America. The Cherokee spoke a type of Iroquoian language from areas to the north and northeast, such as today's upstate New York.

These elements were in play as the Battle of Point Pleasant unfolded. As a result of the defeat of Chief Cornstalk and his warriors, large sections of real estate were surrendered to the victorious forces. This pattern among the Native people had been going on for decades and would continue throughout the 1700s and 1800s.

Even as the Battle of Point Pleasant was being fought, the American Revolution was about to begin in earnest. It has been speculated that Dunmore might have been sabotaging and betraying Col. Lewis’ militia force to weaken these imminent American revolutionaries, potentially soon to be disloyal to the King. Did Dunmore also tip off the Shawnee, who ended up attacking first?

If Dunmore did get a backchannel message to Cornstalk and his warriors, did he give them accurate information about the strength of the militia force? Cornstalk's estimated 300 to 500 warriors attacked the militia force said to have included about 1,000 men. Was Dunmore trying to weaken both adversaries – rebellious colonial militias as well as the Shawnee and Native tribes in the region?

After the battle, many of the militia troops regrouped at the Athens County, Ohio, location of Dunmore’s Fort Gower. There on the mouth of the Hockhocking River, Dunmore forced, or tried to force the militia members to sign a loyalty oath to King and Crown. This loyalty oath is known as the “Fort Gower Resolves.” Many militia troops did not wish to sign such an oath.

But the victory at Point Pleasant for Lord Dunmore was short-lived. Before all the militia troops had even returned home from the Dunmore’s War campaigns against the Shawnee, shots had been fired at Lexington and Concord. The American Revolution had begun. And in 1776, Dunmore was forced out of Virginia by the new “Americans.”

OHIO RIVER VALLEY

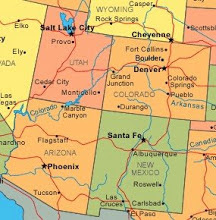

Today, the village of Hockingport is one of the many smaller communities and larger towns along the Ohio River, on both the Ohio and West Virginia sides. Upriver, the Ohio flows through western Pennsylvania. And downstream, the great river continues along Ohio's border with Kentucky, Indiana and beyond before joining the Mississippi River at the southern end of Illinois.

The Hocking River, once a route Dunmore used to attack Shawnee villages, continues northwest from the Ohio about 27 miles to Athens. The town is the county seat of Athens County. It's also home of Ohio University, chartered in 1787 under the new and fragile U.S. government as part of expansion into the Ohio lands, and founded in 1804.

Hockingport is about 27 miles downriver from Marietta, Ohio, which historian David McCullough researched extensively for his best-selling 2019 book “The Pioneers.”

Point Pleasant and the nearby town of Gallipolis, Ohio, are both 45 miles southwest and downriver from Hockingport. In 1966-67, a “UFO flap” occurred around Point Pleasant – one of those situations where odd lights in the sky, and sometimes seemingly-related phenomena, are seen in a particular area in certain time frames.

These have happened throughout the U.S. and around the world. The U.S. Navy is now referring to these airborne types of sightings as “unidentified aerial phenomena” or UAP because they seem to be of different types, some solid, some not.

The 2002 Hollywood movie "The Mothman Prophecies" was based on a limited representation of the best-selling 1975 book by researcher and writer John Keel about the '66-67 situation around Point Pleasant. The movie told only part of the story.

The movie was filmed in the small town of Kittanning on the Allegheny River northeast of Pittsburgh, and in Pittsburgh itself, from where Dunmore launched his assault into those Ohio River Valley lands back in 1774.

Kittanning is the name of a former large town of the Lenape or Delaware people located there. Lenape warriors fought alongside Chief Cornstalk at Point Pleasant. The word "Kittanning" refers to "main river," by which they identified the combined Ohio River and Allegheny River in western Pennsylvania as one river.

The nearby Kittanning Path was a major east-west Native American trail between that region and the higher Appalachian Mountains, and was later used by European colonists.

Many odd, glowing lights around the Point Pleasant region in 1966-67 were seen up and down the Ohio River. And a significant number of such lights were also reported around Point Pleasant's Chief Cornstalk Hunting Grounds, later called the Chief Cornstalk Public Hunting and Fishing Area, and now the 11,772-acre Chief Cornstalk Wildlife Management Area, supervised by the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources.

Could Cornstalk and his Shawnee people be looking in on their old homeland from time to time, remembering that terrible battle at Point Pleasant, and the days and years of struggle and sorrow that followed for the Shawnee and other Native people? Are they able to recall happier times in the Ohiyo lands too?

Are they, like many Americans today, trying to understand and sort out our complex national history – and discover a more perfect union?

(Related articles “Storytelling affects human biology, beliefs, behavior” and “Reagan’s 1987 UN speech on ‘alien threat’ resonates now” are posted on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)