By

Steve Hammons

(This article was posted 4/22/15 on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)

The Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center in Monterey, California,

traces its roots to the secret World War II U.S. Army intelligence unit

comprised of Japanese-Americans – the Military Intelligence Service (MIS).

Then, as now, we needed to succeed militarily and also communicate with other

cultures and nations.

The MIS

was started in late 1941 as a unit to train Japanese-Americans (Nisei) to

conduct translation and interrogation activities. MIS men came mostly from

Hawaii and the West Coast.

The

missions of the MIS were highly classified and still are not widely known. Much

information about MIS activities remained classified until 1972 when President

Richard Nixon signed Executive Order 11652 making certain WWII intelligence

documents eligible for declassification.

After

the Pearl Harbor attack, the people of the United States found themselves in a

war with the military of a culture quite different from our own: Japan. The

Japanese military and Japanese society had, in many ways, a different social

fabric, a different psychology, different spiritual traditions and was a

different ethnic group in significant ways.

MIS

BEGINNINGS

After

Pearl Harbor, first- and second-generation Japanese-Americans in Hawaii and

California faced tough scrutiny by our defense and national security community.

Were there spies and saboteurs among them? Were they loyal to America or Japan,

or torn between the two?

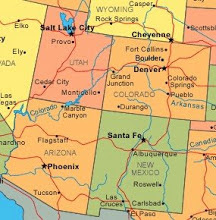

In

California, in part due to racial prejudice and hate-mongering, patriotic

Japanese-American farmers, merchants, professionals and their families were

forced into harsh detention camps in remote regions of the West for the

duration of the war.

In

Hawaii, where Japanese-Americans were well-integrated into the community, there

reportedly were fewer attempts to randomly suspect or imprison them. Nisei

living in Hawaii generally did not experience the extreme measures faced by

those on the West Coast.

Meanwhile,

many young men from these families and communities joined the U.S. military, in

part to prove their patriotism. Many ended up in the MIS as well as the famed

and highly-decorated U.S. Army 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the

100th Infantry Battalion, fighting in Italy and elsewhere in Europe.

They

did all this while many of their family members were behind barbed-wire fences

in detention camps back in the U.S.

Young

Japanese-American men joined the military for many reasons including proving

their loyalty to the United States and proving that they were good Americans.

Many had been raised as somewhat typical American kids.

DEPLOYMENT

AND OPERATIONS

The MIS

organization included an administrative group, an intelligence group, a

counterintelligence group and an operations group. The MIS performed a very

wide range of important and often dangerous activities.

As

American and allied forces moved into the Pacific theater to engage the Japanese

navy and army, MIS men were on the tip of the spear, attached to U.S.

Navy, Army and Marine units as well as the joint Australian-American

"Allied Translator and Interpreter Service." MIS members served with

"Merrill's Marauders," the famous Army Ranger unit that conducted

operations in Burma against the Imperial Japanese Army.

MIS

personnel were active in nearly all major campaigns and battles in the Pacific

as well as in Burma and China.

According

to some assessments, MIS missions may have shortened the Pacific war by up to

two years.

They

performed intelligence and counterintelligence tasks such as intercepting radio

messages, interrogating prisoners, translating captured maps and documents,

helping in psychological and information operations efforts, infiltrating enemy

lines and flushing caves – convincing civilians and Japanese soldiers to leave

caves on remote islands, and persuading many Japanese troops to surrender.

MIS

interrogators reportedly used psychological and cultural understanding to

obtain valuable intelligence. Interestingly, MIS men reportedly provided decent

treatment for Japanese prisoners and obtained information by building rapport

with captured Japanese troops.

After

the war, more than 5,000 MIS personnel worked in Japan during the occupation by

the U.S. from 1945 to 1952. They were assigned to the occupation military

government in disarmament, intelligence, civil affairs, finance, education

and land reform. The MIS also helped develop the Japanese constitution.

LESSONS

LEARNED

The

United States fought a long military struggle in the Pacific. Then, we occupied

Japan with the goal of rebuilding and rehabilitating that society by implementing

a peaceful democracy. Both of these efforts were successful.

Men of

the MIS also demonstrated intelligence and compassion both during the war and

in the occupation. They helped win a military victory, then helped make peace

and win friends for the United States.

They

were key in rebuilding the nation of Japan and helping that society recover

from devastating social, psychological and physical damage.

In

examining the MIS, we must also ask why did these Japanese-American young men,

mostly from the west coast and Hawaii, join the MIS (and the 442nd RCT and

100th Infantry Battalion)? Why did they side with America against the military

of the land of their parents, grandparents and ancestors?

Although most were raised as American kids, they experienced significant racial

prejudice and discriminatory laws. After Pearl Harbor, Japanese American

families had been stripped of property and businesses and forced into the

infamous relocation camps. MIS men emerged out of this environment.

Now may

be the time to review the activities of the MIS and apply lessons learned.

These WWII veterans are now up in years and many have passed on.

Our

special operations forces and intelligence personnel would be wise to consult

these MIS vets whose language and human skills were so crucial in WWII. How did

the MIS conduct their intelligence and rapport-building operations? What can

MIS vets teach us?

As we

deal with global issues today, information about the MIS may provide useful

perspectives.

....................

For more information:

Go For Broke National Education Center website.