At the time, as a high school kid, I did not fully understand that by the date I received my draft card, tens of thousands of American troops had been killed and severely wounded in the Vietnam War. And more were being killed and wounded daily.

That summer, the second year of the draft lottery system was conducted. Like the state gambling lotteries of today, numbers were placed in a large bin and randomly drawn – one number for each of the 365 days in the year that a male baby was born in the year 1952 who turned 18 in 1970.

Those babies, now 18-year-old American males, would be available for the military draft for the Vietnam War. My birthday was picked as #165. I was fairly clueless as to what that meant.

Those draftees were sent directly to Army basic training, then to advanced infantry training and other preparation, and then often to Vietnam and combat.

YOUNG AND DUMB

As it turned out, the “Vietnamization” process of the war had started in 1969 – the U.S. pulling out and handing responsibility to the South Vietnamese government and military.

The draft was winding down. The Selective Service System never did reach #165 of the 1970 batch of bodies to draft, though many 1970 18-year-olds with lower lottery numbers were drafted and went to Vietnam. The Selective Service System drafted up to #125 for that age group.

Americans would be fighting, killing and dying in the Vietnam War for a few years to come before the final withdrawal of combat troops in 1973 (the U.S. embassy was evacuated in 1975 in a chaotic, final pullout.)

The final death toll for American military personnel came to more than 58,000. The vast majority were in their twenties.

There were also significant numbers of American prisoners of war (POWs), more than 1,600 missing in action (MIA) and more than 150,000 injuries.

Vietnam veterans also later suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), other behavioral health issues, alcohol and drug abuse, family problems, homelessness, war-related medical issues (war injuries, exposure to Agent Orange herbicide), incarceration and other problems related to their experiences.

But in the spring 1970 in my senior year of high school, I did not know about all of these factors in motion.

The teenager life of high school, learning to drive, playing football and dating was about to change for me as it had for many before me and after me. I and my peers across the country had now turned 18 and received our draft cards. (And we could now legally buy and drink 3.2 percent "low" beer in Ohio from stores, restaurants and bars.)

But there apparently was a very serious war going on – which we were learning was not totally supported and was seemingly believed by many to be a very bad idea overall – even a war crime.

We were learning that there had been protests, “disturbances” and riots happening on college campuses for the previous few years because of opposition to the Vietnam War.

And that spring, something happened at Kent State University, one of the several medium-size state universities in Ohio. Combat came home when Ohio National Guard troops opened fire on Kent State students protesting the Vietnam War.

As student riots spread, the Ohio governor closed state universities early, sending students home and deploying more National Guard as needed to college campuses to accomplish this. No college graduation ceremonies for the universities' Class of 1970.

VIETNAM WAR AND DRAFT END

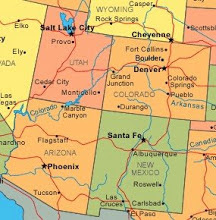

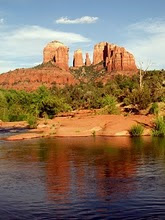

By this time I had informed my “draft board” (local committees who made decisions on who to draft) that I was registered for college the following September at Ohio University in Athens, located in the far southeastern Ohio Appalachian region near West Virginia. My draft status was then changed from 1-H to 2-S (student). My draft lottery number of #165 remained the same.

This was the context in which I had contact with Army Special Forces Reserve personnel in southwestern Ohio in the spring of 1970, still a high school senior, due to somewhat puzzling circumstances.

The next fall I participated in Army Reserve Officers Training Corps in my first year at Ohio University in 1970-71. I also experienced two two-week summer Special Forces Reserve training exercises on either side of that freshman year, summer of ’70 and summer of ’71.

There were robust protests against the war at Ohio University. The storage area under the football stadium bleachers used by the ROTC program had been firebombed in previous antiwar riots.

Opponents of the Vietnam War were saying that old men in Washington, DC, were sending young men off to war in some kind of sick ritual.

People were also saying that lots and lots of money was being made from the Vietnam War and from the blood of our troops and others.

Although I don’t remember the more-recent term “chicken hawk” being used, the idea was the same: Many men (and women) who are very brave about sending other people to kill, die and be severely injured, seemingly don’t want to go themselves or send their own sons and daughters. They wave the flag and beat the drums while other young Americans kill, bleed and die.

In June 1971 the Pentagon Papers about the Vietnam War were published. In June 1972 the Watergate break-in burglars were arrested.

The draft was ended in January 1973, mid-year of my junior year at Ohio U., related to the drawdown of U.S. troops in Vietnam and the significant opposition to the Vietnam War among Americans and internationally.

The final evacuation of the U.S. embassy in Saigon took place April 30, 1975.