By Steve Hammons

In an opinion article published on the Cincinnati Enquirer daily newspaper website Oct. 19, 2018, local retired anthropology professor Sharlotte Neely Donnelly, PhD, shared her insights about the Cherokee.

Donnelly taught at Northern Kentucky University (in the Covington, Kentucky, area of metro Cincinnati), was director of the Native American Studies program there and is the author of “Snowbird Cherokees: People of Persistence” and “Native Nations: The Survival of Fourth World Peoples.”

And in an Oct. 1, 2015, article on the website Slate, history professor Gregory D. Smithers, PhD, also shared information and perspectives about the Cherokee.

Smithers is professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the book "The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity."

Both of these experts on Cherokee culture and history have some interesting things to say about some of the controversies we see today.

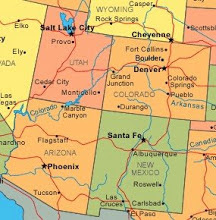

They examine the Cherokee who ended up in "Indian Territory" (Oklahoma) as well as in the ancient homeland region of what is now Kentucky, West Virginia, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama.

RANDOM ACT OF IDENTITY

In Donnelly’s piece, she explores the evolving legal definitions about who is classified as an American Indian or Native American, or Cherokee, by whom, when, where and why.

She wrote, “Who is defined as an American Indian and how much Indian blood quantum (blood degree/ancestry) is required vary over time, from nation to nation (the USA and Canada), from government bureau to bureau (Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of the Census), from state to state, and from tribe to tribe.”

“In the past, the Cherokees, for example, defined anyone who had a Cherokee mother (and thus membership in one of the seven Cherokee clans) as Cherokee [a matrilineal society], despite blood quantum. Beginning in the 1820s, however, anyone with a Cherokee father was also declared a Cherokee, even though such people were clanless,” Donnelly stated.

She also explained some of the bureaucratic inconsistencies. “Some states have no definition of Indianness, while many have less precise definitions than the federal government. Some states, such as South Carolina, with state Indian reservations, are more precise.”

“The state of North Carolina has a government agency to deal with those they recognize as Indian. The federal government recognizes only one North Carolina tribe, the Cherokees, as being Indians while the state recognizes many others, including the Lumbee, Waccamaw Siouans and Haliwas,” according to Donnelly.

She looked at the evolution of these criteria. “In the early 20th century, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina set the minimum blood degree at 1/32 (the equivalent of having one full-blood, great-great-great grandparent) but eventually raised it to 1/16 (the equivalent of having one full-blood, great-great grandparent). When this happened, some Cherokees found they were no longer legally Cherokees.”

“The Keetowah Cherokees in Oklahoma set their minimum even higher, at one-fourth (the equivalent of having one full-blood grandparent), while the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma has done away with blood degree altogether and requires only that one establish lineal Cherokee ancestry to those listed on the Dawes Roll of 1899-1906.”

A person could be an official Cherokee tribal member, but not a Cherokee in the eyes of the U.S. government for certain benefits, Donnelly said. “The United States Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) recognizes the various blood degrees required for tribal membership but requires a minimum of one-fourth for things like higher education grants.”

“So, for example, someone enrolled in North Carolina’s Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians who had a blood quantum of 1/16 to just less than one-fourth would be viewed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs as legally Cherokee but not legally Indian.”

“Canada used to define Indianness as having a father who was recognized as an Indian (mothers did not count) [the reverse of the Cherokee], but in the 1980s Canada switched to a system of blood quantum,” she wrote.

Regarding DNA tests, Donnelly says, “For most Americans with Native American ancestors, that ancestry is five or more generations back. In fact it can be so far back in a family tree that it does not show up in DNA tests. Also, most ancestry testing companies use only a small sample of Native American groups (often less than half a dozen tribes) as a reference for testing, and all of those sample groups tend to be from South, rather than North, America.”

YESTERDAY AND TODAY

In Smithers’ article, he also explores the history and evolution of who is identified as an official Cherokee or other tribal member. He wrote, "At the same time that the Cherokee diaspora was expanding across the country, the federal government began adopting a system of ‘blood quantum’ to determine Native American identity."

"Native Americans were required to prove their Cherokee, or Navajo, or Sioux 'blood' in order to be recognized.”

Smithers explained that, “the federal government’s ‘blood quantum’ standards varied over time, helping to explain why recorded Cherokee 'blood quantum' ranged from 'full-blood' to one 2048th.”

“The system’s larger aim was to determine who was eligible for land allotments following the government’s decision to terminate Native American self-government at the end of the 19th century,” he wrote.

“By 1934, the year that Franklin Roosevelt’s administration adopted the Indian Reorganization Act, 'blood quantum' became the official measure by which the federal government determined Native American identity.” Smithers said.

The decision-makers on these issues evolved, according to Smithers. “In the ensuing decades, Cherokees, like other Native American groups, sought to define ‘blood’ on their own terms.”

“By the mid–20th century, Cherokee and other American Indian activists began joining together to articulate their definitions of American Indian identity and to confront those tens of thousands of Americans who laid claim to being descendants of Native Americans.”

Smithers also explores present-day official Cherokees. “Today, the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Eastern Band of Cherokees comprise a combined population of 344,700.”

“Cherokee tribal governments provide community members with health services, education, and housing assistance.”

“Most Cherokees live in close-knit communities in eastern Oklahoma or the Great Smoky Mountains in North Carolina, but a considerable number live throughout North America and in cities such as New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Toronto. Cherokee people are doctors and lawyers, schoolteachers and academics, tradespeople and minimum-wage workers,” he wrote.

Smithers also noted, “The cultural richness, political visibility, and socioeconomic diversity of the Cherokee people have played a considerable role in keeping the tribe’s identity in the historical consciousness of generation after generation of Americans, whether or not they have Cherokee blood.”

(If you liked this article, please see my other recent ones about the Cherokee on the Joint Recon Study Group and Transcendent TV & Media blogs.)

(Related article

“Storytelling affects human biology, beliefs,

behavior” is posted on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language

and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of

Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)

Friday, February 8, 2019

Story of the Cherokee still emerging today

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)